JOËLLE DUBOIS

GUNDY ROSA INGIMARSDOTTIR

G.KÜNG

HEIDI VOET

Curated by Filip Luyckx

The title of the exhibition comes from a text written by French philosopher Denis Diderot (“This is not a story”, 1772), about two women in confrontation with their respective partners. Nothing is supposedly made up, yet the author does not consider himself able to make a moral judgment about his protagonists. Their social position as well as the actual people in their environment strongly determine their destiny. The writer tells the story to a friend, who himself seems to be well aware of certain facts. Yet what do they actually know? Everything happened more than two decades ago, most of the characters are no longer alive. The story itself became only known posthumously within a broader circle. For generations, it was assumed that the facts were based on reality; some even blamed the author for a lack of imagination. It was only much later that it appeared that the identity of the characters was at least veiled, important facts of life were missing, and the author’s imagination had definitively played an important role. A core of truth remains. The deeper the reader delves into the story, the more he/she is torn between an impression of timelessness on the one hand, and the weight of the historical circumstances on the other. Yet why would fabricated literature reflect reality any less than a retold story that is ultimately based on interpretation? Is not reality largely based on our perception, imagination and wishes? Do we not fabricate entire stories about natural matters, while wondering little about fundamental questions?

Two and a half centuries later, time places this elusive history in a different perspective, or perhaps it doesn’t. People live as children of their time, but even more according to their personal motives. The four female artists in this exhibition set out in search of the point where fiction and reality flow into one another. How do we enter other lives through stories and works of art, to the point that we forget our own momentary situation? Where does anecdote end and the connection with a world consciousness (whatever that may mean) that transcends our limited life experience begin? Can people not simply respond to their personal calling and find harmony with all that exists?

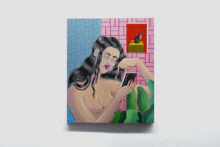

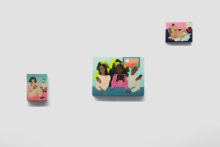

Mental confusion abounds in a society that is fragmented and that has lost the common thread of its life story. In her intimate paintings, Joëlle Dubois uncovers a weak spot in the digital progress. Without any constraint, chatters share their thoughts and passions with partners at a distance. It does not matter whether they are alone or with friends, the focus always lies on those who are virtually present. The sordid eroticism contrasts with the bright colours that are reminiscent of both non-western cultures and Paul Gauguin or Pop Art. The works present popular scenes that are far removed from high culture. They thematise the popular aspect of the Internet where blather and gossip abound. The characterisation of that little intellectual milieu is further enhanced by their clothing, the fast food and the kitschy decor pieces. The ingenious patterns in their clothing and furniture, in turn, refer to pictorial insights. Usually, the artist makes abstraction of time and place. The depicted phenomena are global and encompass a variety of races and cultures. Although the subject is very contemporary, the chatters seem to have exchanged their environment for a timeless digital dimension. They exist somewhere, neither here nor there, in a virtual space in which their whole intimacy is conserved. Their actions are supposedly voluntarily, yet the technical devices are sufficiently titillating to entice the willing consumer. The paintings are similarly attractive and accessible, yet there seems to exist a paradox between the pictorial and the digital promise. The first seduces us aesthetically to look inward, while the gadgetry allows us to become entirely absorbed in artificial hullaballoo.

The sculptures of Georgia Küng depict a mental world that extends beyond the image. Our experience, however, is based on condensed visual elements. Nothing is superfluous; each part potentially contains multiple meanings. The belly-shaped balloons are made up of successive layers of papier-mâché. The time of the creation process is reflected in the fragile material. Shape and surface appear more organic than starkly geometric, their appearance is very physical. The concave form refers to the pear-shaped uterus, the cradle of physical life. At the same time, the negative cavity points to the aspect of potentiality; it is the woman herself who decides about her pregnancy. We look at a fragile cocoon, reminiscent of the outer shell of a turtle, that offers protection to unconscious life. The material structure resembles an archaeological object that comprises several time layers, or a geological stratification that evolves without the interference of man. Life processes are predominantly controlled by nature according to age-old patterns. The spheres also represent the earth, or are they domes as symbols of the universe? Later in life, our consciousness plays an increasingly important role, so the spheres also function as brains. Yet consciousness can hardly be defined, it exists just as well outside of our brain, through our entire body, in connection with our close and distant surroundings. The spheres also suggest other time frames and dimensions with great creative potential. Where do our dreams come from and what do we do with them? Countless girls dream of being able to ride away on their own horses. This desire seems to be both innate as well as reinforced through upbringing and the visual industry. The horse, however, remains a metaphor for speed and strength, the sensation of freedom, of a woman who follows the thread of her fantasy.

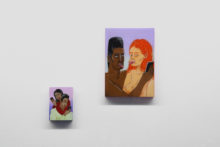

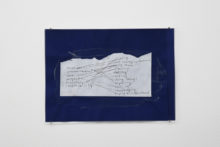

The drawings by Gudny Rosa Ingimarsdottir present in their apparent simplicity a variety of visual elements. The artist makes full use of the intrinsic qualities of the paper, such as the colour, the texture and the edge. She seeks to strike a balance between her visual intervention and the empty surfaces. Sparingly, she uses fragments derived from various visual systems in the drawings: graphics, photography, language, typography, but even more from the manipulation of the paper itself. This is evidenced in the collage of fragments, as well as the application of paint and transparent paper. In this way, she composes her own fragmented reality, partly abstract and partly suggestive. There is always the impression that we are looking at a part of a larger whole that extends beyond the edges of the picture. Here and there, organic forms appear that possibly refer to the body, to animals, stones, textiles or utensils. The tactile nature of this amalgam makes that the viewer becomes physically engaged with the work. Greater, still, is the mental involvement that invites the viewer to engage with the artist’s experience of time. We look, as it were, at the time of the maker, whether it is the artist or a fictional character. The drawings are reminiscent of manuscripts and notes that have been heavily worked on. Subsequently, the work becomes affected by time, and, embodying both the time of the artist as well as the passing of time itself, manifests itself to the spectator. Since the drawings reveal multiple layers of time experience, the observer is invited to explore this temporal intensity within him or herself. This endeavour is endless; between the many layers of the work, there are many imaginary time zones that appear to be virtually limitless. The story can go in countless directions.

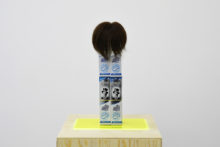

The global consumer culture stimulates the momentary gaze. Heidi Voet transforms the superficial lustre of such products into sculptures that tell a story about attraction, manipulation of human behaviour, economy and power relations. To do so, she uses specific articles that she combines with suggestive titles. The products are aimed at a broader middle class audience that is looking for an exclusive touch. Often, these products aim to enhance the appearance of women according to global standards. The exhibition presents a copy from the series “The Abduction/I am beautiful/ Carnal Love/The Cat”. The title refers to various names given to an erotic sculpture by Auguste Rodin from the “Gates of Hell”, in which a naked man upholds a crouching woman. The sculptures in the exhibition consist of eight tubes of toothpaste adorned with a wig made of human hair. Both the products and the spectators are reflected in a sheet of Plexiglas. They evoke a desire for a prosthetic metamorphosis. The brand names of the toothpaste “White Men” and “Darlie” (formerly “Darkie”) express male dominance. The international nature of these objects does not prevent women from projecting their self-conscious desire onto status symbols that are essentially defined by white men. Such striking details also express the way roles are assigned and the real power relations on a global scale. Does the title hold the promise of the ultimate recognition of the female consumer, or does he rather open the gates of hell?

“Peer Pressure” consists of a series of twelve prints in which pieces of fruit are seen to change colours. The images have an artificial character; they were taken from their natural setting and abstracted to become attractive consumption fetishes. This desire to change skin does not only refer to body prosthesis but also to processes of acculturation. Many native fruit species thrive far from their countries of origin. The associations between their old and new biotope are fading. That in itself is not comical, but the fact that they obsessively try to assume the identity of an assimilating culture, is. This not always involves a functional adjustment, but rather a conforming to the most glorious aspects of that culture. The latter is the product of perception, which is maintained through media, publicity and education. The personal story is unperceivably permeated by stories of economy and power.

– Filip Luyckx

Curator of Sint-Lukas Gallery, Brussels (BE)

Read more about Joëlle Dubois, Gudny Rosa Ingimarsdottir, G.Küng and Heidi Voet