Eirene Efstathiou

What has happened to the state of contemporary politics? Wasn’t there once a time when politicians were driven primarily by unselfish motives or altruistic intentions and entered politics to serve the public good –a time when politicians were well-educated people, bound by moral integrity and high ideals? True, politics has always been prone to corruption and the abuse of power, but in recent years it seems that self-serving private interests – or the interests of industry and business – have come to take precedence over the interests of the wider electorate. Citizens, it seems, exist only to be managed, manipulated and exploited, rather than served. Political campaigns deliver messages of fear, rather than of hope; scandals abound and miscreants offer apologies without sincerity and then quickly return to ‘business as usual’. Voting is no longer about positive choice, but about accepting the lesser of two evils. No wonder then that fewer and fewer people are turning out to vote.

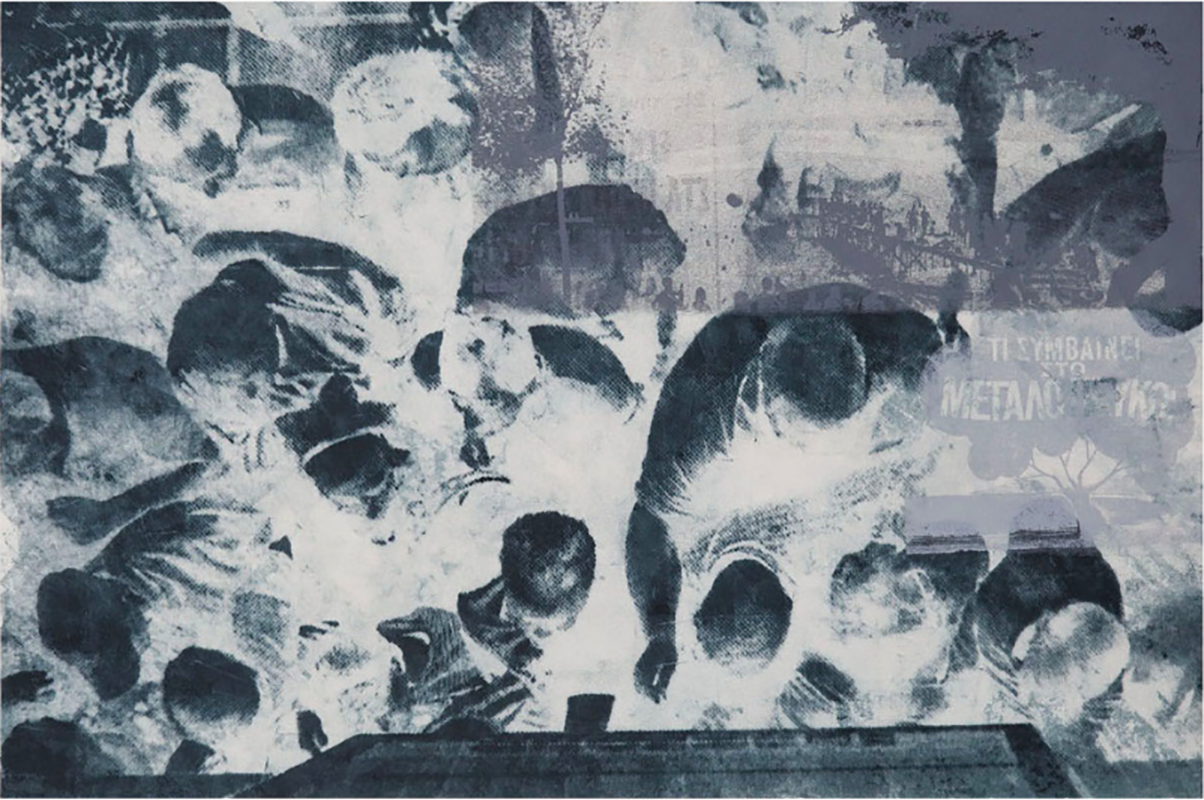

In addition, we have witnessed the debasement of political language, the infantilisation and polarisation of debate, and the growth of a simplified discourse that panders to collective fears rather than addressing the real, pressing questions. Welcome to the heydey of ‘psychopolitics’ – the interaction between politics or political phenomena and human psychology. With Trump in the White House and Putin in the Kremlin, psychopolitics has taken on a new, frightening, meaning. No wonder so many of us feel disillusioned. Philosopher Lieven de Cauter calls this sense of disillusionment ‘political melancholy’: a sinking feeling borne from frustration, anger, despair, mistrust, sadness and hopelessness. (This exhibition is inspired by his text Small Anatomy of Political Melancholy.) (1) The disillusionment with politics, government, state institutions and political parties is at an all-time high. For the first time since World War II (which was preceded by similar political crises of the 1920s and 1930s), we have reason to fear the disintegration of peace and the rise of aggressive nationalism.

Clearly there is something profoundly wrong with contemporary politics: not only the moral and intellectual inadequacy of politicians, but also the gaping chasm between the aims of politicians and the needs of citizens. The foundations of democracy itself are at risk, not only from the rise of demagogic populism in Europe, but also from the grip of financial institutions and mega-corporations. Greece, of course, exemplifies the loss of sovereignty due to debt, where ordinary citizens have been forced to bail out a country driven to financial collapse by government mismanagement. The longstanding economic and political crisis in Greece has led to political disillusionment, mistrust of institutions, and a sense of collective powerlessness, and a post-ideological phase characterized by apathy, individualism, and resignation. According to sociologist of law Ioannis Kampourakis: “This defeatism fits into a longer trend in Greece, tracing back to the defeat of the communist left after the post-WWII Civil War, of nostalgia and glorification of a ‘struggle fought, even if lost’, which has aestheticized the contemporary apathy as a form of political pessimism and melancholy.” (2)

The artists in the exhibition Anatomy of Political Melancholy probe this phenomenon and reveal its complexities, translating it into resonant images. How did we get where we are? Can we imagine a way out? Anatomy of Political Melancholy probes and condenses the present condition – often mistaken as one that is also the product of the consumerist ‘politics of content’. Studies suggest the exact opposite: a politics of disillusionment sue to the status quo. The exhibition highlights the dangers of political apathy and points to the fact that – contrary to what neoliberal discourse says – there are still such things as society and community. It is too easy to become resigned to the present malaise, to become merely cynical. However, as writer and activist George Monbiot argues, the stirrings of a new sociocracy are in the making (3). And there are alternatives.

Some of the things Monbiot suggests – the radical reform of political campaign finance and limitations on the power of corporations to buy political space; assistance to enable voters make better-informed choices – already exist. In Germany, for example, the federal agency for civic education publishes authoritative and accessible guides to the key political issues, and tries to engage with groups that usually shun democratic politics. Another example is Switzerland, with its Smartvote system, which presents a list of policy choices with which one can agree or disagree, then compares one’s answers with the policies of the parties and candidates contesting the election.(4) Monbiot suggests that a new method, ‘sociocracy’, could enhance democracy. This is a system designed to produce inclusive but unanimous decisions, by encouraging members of a group to continue objecting to a proposal until, between them, they produce an answer all of them can live with. It is clear that political practice has to be rethought, not in representing pre-constituted identities, but rather in constituting those identities. This requires new ways of unorthodox political thinking, a new sense of urgency about democracy’s strengths and weaknesses, and an open discussion about the pros and cons of liberal democracy. Anatomy of Political Melancholy thus attempts the difficult task of both capturing the complexity of the moment and imagining a better future.

– Katerina Gregos, curator

Notes:

1. Lieven de Cauter, Small Anatomy of Political Melancholy

http://crisiscritique.org/special09/cauter.pdf

2. Ioannis Kampourakis, Political disillusionment in Greece: toward a post-political state?

https://www.opendemocracy.net/can-europe-make-it/ioannis-kampourakis/political-disillusionment-in-greece-toward-post-political-state

3. George Monbiot, Our democracy is broken, debased and distrusted – but there are ways to fix it

https://www.theguardian.com/commentisfree/2017/jan/25/democracy-broken-distrusted-trump-brexit-political-system

4. These are, of course, mature European societies, which is a prerequisite for the application of such new models. It requires creating the conditions for a new political education and a new political culture.

Afterthought: The political lethargy of citizens – a consequence of politicians’ disinterest in real and urgent socio-political and cultural problems – is indeed obvious. But plausible solutions are far less obvious. Our present pessimism, resignation and apathy could instead provide a strong and positive incentive to think again about certain deeply felt injustices in society. The current state of affairs is precisely the reason we should try to square the circle of practical possibility and ideal imaginary, of pessimism and hope. It is high time that we stopped banging our heads against the wall and made a serious attempt at rigorous analysis and the explication of the possible roads out of our predicament. This exhibition is both relevant and urgent. It picks up on a debate that witnessed all around us, every day, in Greece, in Europe, and globally.

Read more about Eirene Efstathiou